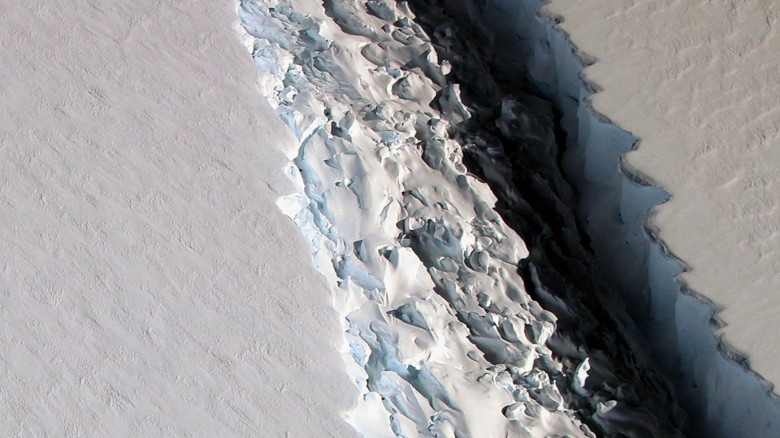

Massive iceberg breaks away from Antarctica

(CNN)This week, a trillion-ton hunk of ice broke off Antarctica.

You probably know that. It was all over the Internet.

Among the details that have been repeated ad nauseam: The iceberg is nearly the size of Delaware, which prompted some fun musing on Twitter about where exactly Delaware is and how anyone is supposed to approximate the square footage of that US state. The ice, which has been named A68, represents more than 12% of the Larsen C ice shelf, a sliver on the Antarctic Peninsula. And most important: None of this has anything to do with man-made climate change.

The problem: That last detail -- the climate one -- is misleading at best.

At worst, it's wrong.

ADVERTISING

Some scientists think this has a lot to do with global warming.

I spent most of Thursday on the phone with scientists, talking to them about the huge iceberg off Antarctica and what it means. Here are my five takeaways.

1. This doesn't NOT look like climate change.

There is no disagreement among climate scientists about whether humans are warming the Earth by burning fossil fuels and polluting the atmosphere with greenhouse gases. We are. And we see the consequences.

But there is some dispute about whether there is enough evidence to tie the breakoff of this particular piece of ice to global warming.

In a widely quoted statement, Martin O'Leary, a Swansea University glaciologist who was part of the team studying Larsen C, said that the iceberg calving was "a natural event" and that "we're not aware of any link to human-induced climate change."

Not everyone agrees with that assessment, however.

At 6,000 square kilometers, the Larsen C ice sheet could be one of the world's biggest ever icebergs.

Source: European Space Agency

"They're looking at it through a microscope" rather than seeing macro trends, including the fact that oceans around Antarctica are warming, helping thin the ice, said Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished senior scientist at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research.

"To me, it's an unequivocal signature of the impact of climate change on Larsen C," said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of California, Irvine. "This is not a natural cycle. This is the response of the system to a warmer climate from the top and from the bottom. Nothing else can cause this."

Rignot said colleagues who say otherwise are burying their heads "in the ice."

2. That said, this s*** is complicated.

The difference in opinion stems, in part, from a perceived lack of data. Compared with other parts of the world, Antarctica is cold, weird, remote and hard to study. Some scientists say they don't have the super-long-term datasets they would need to prove that man-made warming affected this particular ice sheet.

Conversely, they can't disprove global warming's contribution, either.

"I myself don't see clear evidence convincing me that this is climate change-related," said Christopher Shuman, a research scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. "I think we need to wait and see. We need to watch carefully and wait for the signs."

If the Larsen C ice shelf continues to collapse, he said, we'll know that climate change had something to do with this week's events. If not, his theory will be confirmed, meaning the iceberg is part of a natural cycle of calving and regeneration.

Nearby ice sheets with similar names -- Larsen A and B -- broke down for reasons that are related to climate change, Shuman said. The cause of Larsen C's break this week is less clear, he said, because it's winter in the Antarctic now; there was no evidence of meltwater on the surface of the iceberg, and there aren't enough data about temperature trends in that area, both in the water and in the air.

Rignot, the scientist in California, said the fact that this collapse happened during the dead of winter in the Southern Hemisphere makes it all the more remarkable.

He sees the broader collapse of the Larsen C ice shelf as inevitable.

The question for him is when: likely 10, 20, maybe 30 years, he said.

3. Climate change certainly is reshaping Antarctica.

Further complicating things, climate change is reshaping Earth's southernmost continent in a variety of ways. Air temperatures have risen over the Antarctic Peninsula, where Larsen C is located, said David Vaughan, director of science at the British Antarctic Survey, but not as much in other locations.

Ocean temperatures are up worldwide too, including near Antarctica, he said. "The amount of heat that's going into the ocean is really huge," Trenberth said.

That's helping thaw some of the ice from above and below. Ice that touches the water is thought to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of global warming. But, again, Antarctica is big and cold and weird. It's not melting as quickly as ice in the Arctic, where temperatures are rising about twice as fast as the global average.

It's clear that some ice sheets in Antarctica are melting because of climate change and that some glaciers are getting thinner, researchers told me. The question is whether there are sufficient data to say that this particular iceberg was broken off because of greenhouse gas pollution.

"Do I believe that's a climate change impact? Probably. Not 100%," said Vaughan, of the British Antarctic Survey. "But the reason the warm water comes onto the continental shelf at all is because of the winds that blow across the southern ocean, and we believe the winds have gotten more intense because of climate change.

"This is not straightforward," he added. "It's simply not as straightforward as 'the temperature rises and the ice melts.' It's a whole chain of quite subtle and very consecutive processes that cause the ice to melt and the sea levels to rise."

So, again, it's complicated.

But step back from the microscope: Greenhouse gas pollution is contributing to warming and melting.

4. The type of ice you're talking about matters.

To better understand the ice in Antarctica, imagine a cocktail glass with ice and liquid in it. What happens to the level of the drink as the ice melts?

"When my ice melts, the cocktail doesn't overflow," said Rignot, the glaciologist. The surface stays about level.

This type of ice -- the floating-in-water kind -- is what broke off into the ocean this week in Antarctica. Scientists call it an "ice shelf." As opposed to a glaciers or ice sheets, which are found on land, floating ice shelves don't raise global sea levels appreciably when they break off into the ocean and melt.

Again, think of the cocktail glass.

But -- and this is an important "but" -- those floating ice shelves often have a "buttressing effect" on inland ice masses that will raise global sea levels if they melt, said Trenberth, the climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. As that fringe of ice goes, it can help to start destabilizing the middle.

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

South Africa – The carcass of a dead cow lies in the Black Umfolozi River, dry from the effects of a severe drought, in Nongoma district north west from Durban, in November 2015. South Africa ranks as the 30th driest country in the world and is considered a water-scarce region. A highly variable climate causes uneven distribution of rainfall, making droughts even more extreme.

Hide Caption

8 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Sudan – A gigantic cloud of dust known as "Haboob" advances over Sudan's capital, Khartoum. Moving like a thick wall, it carries sand and dust burying homes, while increasing evaporation in a region that's struggling to preserve water supplies. Experts say that without quick intervention, parts of the African country -- one of the most vulnerable in the world -- could become uninhabitable as a result of climate change.

Hide Caption

9 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Maldives – Low tide reveals the extent of accelerated erosion shown by the amount of exposed beach rocks on Maafushi beach in the Maldives. This is the world's lowest-lying country, with no part lying more than six feet above sea level. The island nation's future is under threat from anticipated global sea level rise, with many of its islands already suffering from coastal erosion.

Hide Caption

10 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Argentina – Los Glaciares National Park, part of the third largest ice field in the world, on November 27, 2015 in Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. The majority of the almost 50 large glaciers in the park have been retreating during the past 50 years due to warming temperatures, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

Hide Caption

11 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Kenya – A boy from the remote Turkana tribe in Northern Kenya walks across a dried up river near Lodwar, Kenya. Millions of people across Africa are facing a critical shortage of water and food, a situation made worse by climate change.

Hide Caption

12 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

India – An Indian farmer in a dried up cotton field in the southern Indian state of Telangana, in April 2016. Much of India is reeling from a heat wave and severe drought conditions that have decimated crops, killed livestock and left at least 330 million people without enough water for their daily needs.

Hide Caption

13 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Honduras – Strawberries lost due to a fungus that experts report is caused by climate change in La Tigra, Honduras, in September 2016. According to Germanwatch's Global Climate Risk Index, Honduras ranks among the countries most affected by climate change.

Hide Caption

14 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Florida – A flooded street in Miami Beach in September 2015. The flood was caused by a combination of seasonal high tides and what many believe is a rise in sea levels due to climate change. Miami Beach has already built miles of seawalls and has embarked on a five-year, $400 million stormwater pump program to keep the ocean waters from inundating the city.

Hide Caption

1 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Virginia – Sea water collects in front of a home in Tangier, Virginia, in May 2017. Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay has lost two-thirds of its landmass since 1850. Now, the 1.2 square mile island is suffering from floods and erosion and is slowly sinking. A paper published in the journal Scientific Reports states that "the citizens of Tangier may become among the first climate change refugees in the continental USA."

Hide Caption

2 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Austria – The Pasterze glacier is Austria's largest and it's shrinking rapidly: the sign on the trail indicates where the foot of the glacier reached in 2015, a year before this photo was taken. The European Environmental Agency predicts the volume of European glaciers will decline by between 22 percent and 89 percent by 2100, depending on the future intensity of greenhouse gases.

Hide Caption

3 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Greenland – A NASA research aircraft flies over retreating glaciers on the Upper Baffin Bay coast of Greenland. Scientists say the Arctic is one of the regions hit hardest by climate change.

Hide Caption

4 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Switzerland – A wooden pole that had been driven into the ice the year before now stands exposed as the Aletsch glacier melts and sinks at a rate of about 10-13 meters per year near Bettmeralp, Switzerland.

Hide Caption

5 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Louisiana – In the Mississippi Delta, trees are withering away because of rising saltwater, creating "Ghost Forests."

Hide Caption

6 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

California – A street is flooded in Sun Valley, Southern California in February 2017. Powerful storms have swept Southern California after years of severe drought, in a "drought-to-deluge" cycle that some believe is consistent with the consequences of global warming.

Hide Caption

7 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

South Africa – The carcass of a dead cow lies in the Black Umfolozi River, dry from the effects of a severe drought, in Nongoma district north west from Durban, in November 2015. South Africa ranks as the 30th driest country in the world and is considered a water-scarce region. A highly variable climate causes uneven distribution of rainfall, making droughts even more extreme.

Hide Caption

8 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Sudan – A gigantic cloud of dust known as "Haboob" advances over Sudan's capital, Khartoum. Moving like a thick wall, it carries sand and dust burying homes, while increasing evaporation in a region that's struggling to preserve water supplies. Experts say that without quick intervention, parts of the African country -- one of the most vulnerable in the world -- could become uninhabitable as a result of climate change.

Hide Caption

9 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Maldives – Low tide reveals the extent of accelerated erosion shown by the amount of exposed beach rocks on Maafushi beach in the Maldives. This is the world's lowest-lying country, with no part lying more than six feet above sea level. The island nation's future is under threat from anticipated global sea level rise, with many of its islands already suffering from coastal erosion.

Hide Caption

10 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Argentina – Los Glaciares National Park, part of the third largest ice field in the world, on November 27, 2015 in Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. The majority of the almost 50 large glaciers in the park have been retreating during the past 50 years due to warming temperatures, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

Hide Caption

11 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Kenya – A boy from the remote Turkana tribe in Northern Kenya walks across a dried up river near Lodwar, Kenya. Millions of people across Africa are facing a critical shortage of water and food, a situation made worse by climate change.

Hide Caption

12 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

India – An Indian farmer in a dried up cotton field in the southern Indian state of Telangana, in April 2016. Much of India is reeling from a heat wave and severe drought conditions that have decimated crops, killed livestock and left at least 330 million people without enough water for their daily needs.

Hide Caption

13 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Honduras – Strawberries lost due to a fungus that experts report is caused by climate change in La Tigra, Honduras, in September 2016. According to Germanwatch's Global Climate Risk Index, Honduras ranks among the countries most affected by climate change.

Hide Caption

14 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Florida – A flooded street in Miami Beach in September 2015. The flood was caused by a combination of seasonal high tides and what many believe is a rise in sea levels due to climate change. Miami Beach has already built miles of seawalls and has embarked on a five-year, $400 million stormwater pump program to keep the ocean waters from inundating the city.

Hide Caption

1 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Virginia – Sea water collects in front of a home in Tangier, Virginia, in May 2017. Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay has lost two-thirds of its landmass since 1850. Now, the 1.2 square mile island is suffering from floods and erosion and is slowly sinking. A paper published in the journal Scientific Reports states that "the citizens of Tangier may become among the first climate change refugees in the continental USA."

Hide Caption

2 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Austria – The Pasterze glacier is Austria's largest and it's shrinking rapidly: the sign on the trail indicates where the foot of the glacier reached in 2015, a year before this photo was taken. The European Environmental Agency predicts the volume of European glaciers will decline by between 22 percent and 89 percent by 2100, depending on the future intensity of greenhouse gases.

Hide Caption

3 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Greenland – A NASA research aircraft flies over retreating glaciers on the Upper Baffin Bay coast of Greenland. Scientists say the Arctic is one of the regions hit hardest by climate change.

Hide Caption

4 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Switzerland – A wooden pole that had been driven into the ice the year before now stands exposed as the Aletsch glacier melts and sinks at a rate of about 10-13 meters per year near Bettmeralp, Switzerland.

Hide Caption

5 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

Louisiana – In the Mississippi Delta, trees are withering away because of rising saltwater, creating "Ghost Forests."

Hide Caption

6 of 14

Photos: The effects of climate change on the world

California – A street is flooded in Sun Valley, Southern California in February 2017. Powerful storms have swept Southern California after years of severe drought, in a "drought-to-deluge" cycle that some believe is consistent with the consequences of global warming.

Hide Caption

7 of 14

So while scientists are right to say the Larsen C iceberg won't change global sea levels in a literal and immediate sense, the big picture may be less rosy and simplistic.

"Floating ice doesn't change sea level at all," Trenberth said, "but the consequences of this may well end up increasing sea level quite substantially in the long term."

Already, global sea levels are up about 8 centimeters since 1992, largely because of global warming, he said. And they're rising at a rate of 3.4 millimeters per year.

5. But it's clear that melting Antarctic ice is a multigenerational time bomb.

Those numbers probably sound small. They are small. Who cares about a few millimeters of difference in the tides?

But this reveals yet another failing in the way most of us are talking about the melting of the world's ice: We must force ourselves to think on bigger timescales.

We should think about New York, Miami, Shanghai and other coastal cities threatened by rising seas in our lifetimes. I can't write about this issue without remembering my trip to the Marshall Islands, a tiny island nation in the Pacific that stands to lose all of its territory -- and language, culture and history -- if temperatures rise just 2 degrees Celsius, which seems increasingly likely.

But we must also consider future generations. What kind of world are we dumping on them?

When you think in terms of decades or centuries, the most vulnerable part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could raise global sea levels as much as 3 meters, Rignot told me. And the larger East Antarctic Ice Sheet, in the very long term, could lift tides 19 meters, he said. That's more than 62 feet, or a building that's at least six stories tall.

"The actions we're taking now actually have consequences 50 years from now, 100 years from now -- and 200 years from now," Trenberth said.

When we see trillion-ton ice chunks falling off a continent, that's well worth remembering.