Bangladesh gets less than guaranteed Ganges water

India deprived Bangladesh of its guaranteed Ganges water share for 65 per cent time during the critical dry periods in violation of an agreement signed between the two countries 23 years ago.

A statistical analysis of the post-treaty data (1997–2016) indicates that ‘65% of the time Bangladesh did not receive its guaranteed share during the critical dry periods with high water demand,’ according to a study conducted by a four-member panel of foreign and local experts.

When asked about the observations and analysis made in the study, KM Anwar Hossain, member of the Joint Rivers Commission, Bangladesh, said, ‘Low-flow events might happen due to water shortages during the dry seasons.’

Bangladesh and India signed the treaty in 1996 on sharing of ‘the Ganges Waters at Farakka’ for 30 years.

Sheikh Hasina, then Bangladesh prime minister, and her Indian counterpart HD Deve Gowda signed the treaty on behalf of their respective governments in the wake of unilateral withdrawal of water from the common rivers upstream in India.

The study styled as ‘A critical review of the Ganges Water Sharing arrangement’ was jointly conducted by Fulco Ludwig and Kazi Saidur Rahman of Wageningen University and Research of the Netherlands, Zahidul Islam of Alberta Environment and Parks of Canada, and Umme Kulsum Navera of the Department of Water Resources Engineering of the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology in Dhaka.

The study was published under the Creative Commons arrangements earlier this year.

The research made an evaluation of the cooperation [between India and Bangladesh] reflected in the treaty by making a quantitative analysis on available water sharing data.

‘Our statistical analyses of recent flow data at Farakka [in India] and the Hardinge Bridge [in Bangladesh] showed that Bangladesh frequently did not receive its [fair] share during the most critical periods of the dry season when water demand is relatively high in both countries,’ the study report said.

Then the report went on, ‘We suggest providing a guarantee clause to safeguard the fair share of Bangladesh during the occurrences of extreme low-flow events.’

Results of the analysis also show that substantially lower quantities of water than the indicative share as per the treaty were released to Bangladesh during the six critical periods from March 11 to May 10.

During the March 21–31 cycle in the year 2010, the actual release to Bangladesh was only 474 cubic-metres per second, which was 44 per cent lower than the indicative release of 841 cubic-metres per second.

Such failures in ensuring the minimum guaranteed flows to Bangladesh occurred frequently during the most critical periods over several recent drier years between 2008 and 2011.

The analysis shows that Bangladesh did not receive its guaranteed 991 cubic-metres per second flow for 10 out of the 12 alternate events between 2008 and 2011.

There were further 38 per cent and 36 per cent decreases in 10-day average flows during the other alternate critical periods of April 11–20 and May 1–10 in 2010 respectively, which confirmed a consistent lower share for Bangladesh.

The situation became even worse in 2016 than in 2010.

The actual release during March 21–31, 2016 was only 442 cubic-metres per second, which was 47 per cent lower than the indicative share, followed by 34 per cent and 49 per cent decreases in the flows during the other alternate critical periods respectively.

Most of the times the flows at the Hardinge Bridge were recorded as unusually lower than the stipulated releases from Farakka.

In 2010, for instance, the flows at the Hardinge Bridge during the three alternate 10-day cycles were nine per cent (March 11–20), 38 per cent (April 1–10) and 21 per cent (April 21–30) lower than the stipulated release of 991 cubic-metres per second from Farakka.

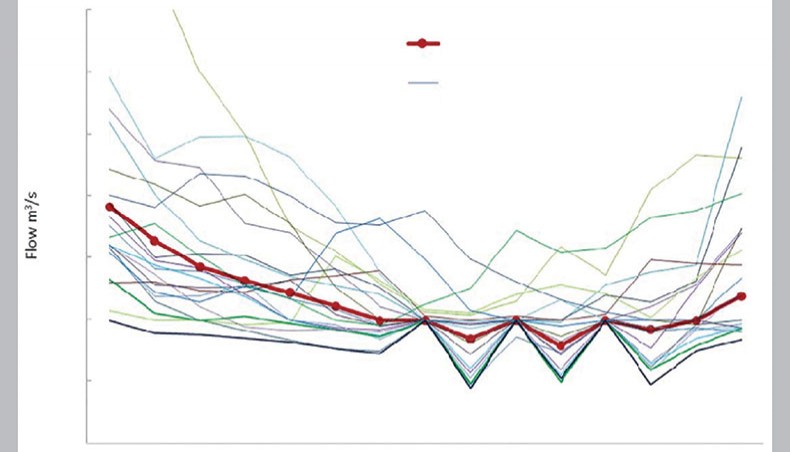

The actual yearly releases from Farakka and the corresponding flows at the Hardinge Bridge were also compared during the post-treaty period (1997–2016).

The results reveal that overall 31 per cent of the times (94 out of 300 events) Bangladesh received less water at Hardinge Bridge compared to presumably what was released from Farakka.

Furthermore, the failure rate was relatively much higher during the critical periods when Bangladesh was guaranteed to receive 991 cubic-metres per second flows for each 10-day cycle.

The experts claimed that they systematically reviewed the outcome of the treaty with quantitative analysis of dry-season availability of the Ganges flows at the Farakka and Hardinge Bridge points.

The review indicates that the major barriers to a successful implementation of the treaty are ‘inaccurate projection of future available flows at Farakka’, ‘inappropriate provision of guaranteed flow during critical dry periods’, ‘inadequate protection of flows at Hardinge Bridge’, ‘lack of guarantee clause for Bangladesh’ and ‘no consideration of environmental and economic drivers’.

They said that the 1996 treaty did not have a distinct guarantee clause similar to the 1977 Agreement which ensured that Bangladesh received a minimum of 80 per cent of the scheduled flow during extremely low-flow events at Farakka.

However, the treaty indirectly ensured that Bangladesh could obtain at least 90 per cent of the share stipulated in the treaty in case there were no mutual agreements on sharing arrangement during the review process.

‘Thus, it is inferred that the treaty recognised the necessity of guaranteed flows for Bangladesh to safeguard its fair share in the event of substantial reduction of flows at Farakka,’ they said.

The tenure of the present treaty will expire in 2026 after the completion of its 30 years of operation.

The study results indicate that the treaty underestimated the impact of climate variability and the possibility of increasing upstream water extraction.

Since the availability of Ganges flow at Farakka depends on the climatic conditions of the basin, it is necessary to analyse the basin rainfalls and their trends for different time-scales, they said.

The panel also advised on projecting the reliable water availability using a combination of modelling and improved observation of river flows.

The Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) river system is the third largest freshwater outlet to the world’s oceans, being exceeded only by the Amazon and the Congo River systems (Chowdhury & Ward, 2004).

Within the GBM river system, 54 common rivers cross the border between upstream India and downstream Bangladesh.

Only one of these rivers, the Ganges, is subject to a bilateral agreement between the two countries.

When India commissioned the Farakka Barrage (just upstream of the India–Bangladesh Border) on the Ganges in 1975, the dry season flow into Bangladesh reduced significantly.

This eventually resulted in a dispute over the sharing of the dry season flow between the two countries.

News Courtesy: www.newagebd.net