A new life for the Rohingya

They’ve been streaming in by the thousands each day: Rohingya Muslims fleeing violence in Myanmar and finding refuge across the border in Bangladesh.

More than 500,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar since late August, creating “a humanitarian and human rights nightmare,” according to Antonio Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations.

Witnessing this firsthand was Italian photographer Antonio Faccilongo, who spent two weeks in Bangladesh taking photos for Doctors Without Borders, one of the many aid organizations in the area.

Faccilongo followed refugees as they made a new home in a new country. His photos reflect the poor living conditions in camps, but he said many of the people he met were just glad to finally be safe.

“They are not ambitious. They just need a tent and some food and they are happy,” he said.

Children sleep inside a tent at one of the refugee camps in Bangladesh.

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority who come from Myanmar’s Rakhine State but are not recognized there as citizens. They are considered by many human rights groups to be among the world's most persecuted people.

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya were already in Bangladesh before the recent exodus that began in late August. On August 25, Rohingya militants killed 12 security officers in coordinated attacks on border posts, according to Myanmar’s state media. The military responded with intensified “clearance operations” against “terrorists,” driving thousands of people from their homes. Satellite photos released by Human Rights Watch showed entire villages torched to the ground.

UN human rights chief Zeid Ra'ad al-Hussein called the Rohingya crisis a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” Myanmar’s government has denied this claim, saying they are fighting terrorists and taking “full measures to avoid collateral damage and the harming of innocent civilians.”

Men reach for a jug during an unofficial water distribution. “When the water cans were almost (gone), I saw two men struggling to win one,” Faccilongo recalled. “The meaning of that struggle was to be able to give water to their own family to survive. It was very painful. In the Western countries, we have water at any moment we want. It is a primary good guaranteed to everyone. Inevitably this makes me feel guilty. Even more so because I had a canteen in my backpack, which after a few hours I could fill again.”

During his stay in Bangladesh, Faccilongo said he met many Rohingya who faced violence crossing the border or before leaving Myanmar. Some of their family members were killed or badly hurt.

“They often invite me in their tents to tell their story or just to see a Western white man with a lot of clothes and photographic equipment that, in their eyes, is really strange. But the trauma hidden behind their smiles occasionally emerges,” he said. “For example, on more than one occasion when I tried to play with the kids, with delicacy ... they just got frightened by seeing me approach.”

The refugees have been welcomed by Bangladesh and by nongovernmental organizations that are set up to help provide food, water, medical care and other necessities. But they face an uncertain future. They have little to no money, Faccilongo said, and it remains to be seen where they will ultimately end up.

A man lies on the floor of a house in Bangladesh. Faccilongo was told the man became paralyzed after being attacked and beaten by Myanmar soldiers as he crossed the border.

Faccilongo met one woman who was afraid that when she left the hospital, she would no longer receive help from the aid organizations or be able to build her tent.

“I gave her the equivalent of 50 euros to help her in the early days outside the hospital,” he said. “She looked me straight in the eyes and with a kindly tone of voice told me that perhaps now that she is rich her husband would return to them and she would open a small shop.

“It's amazing how the equivalent of a dinner for two people in the Western (world) equates to the hope of a better life.”

Rohingya refugees set up a new refugee camp in Bangladesh.

Workers build a new Doctors Without Borders clinic in the Balu Khali refugee camp, which is in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

A child’s height is measured at one of the refugee camps. Faccilongo said symptoms of post-traumatic stress are most evident in children.

Rohingya patients rest at a clinic in the Kutupalong refugee camp.

A boy bathes in one of the refugee camps.

Sellers from a local market. Faccilongo said the refugees don’t have much money.

Men bury their mother in the Kutupalong refugee camp.

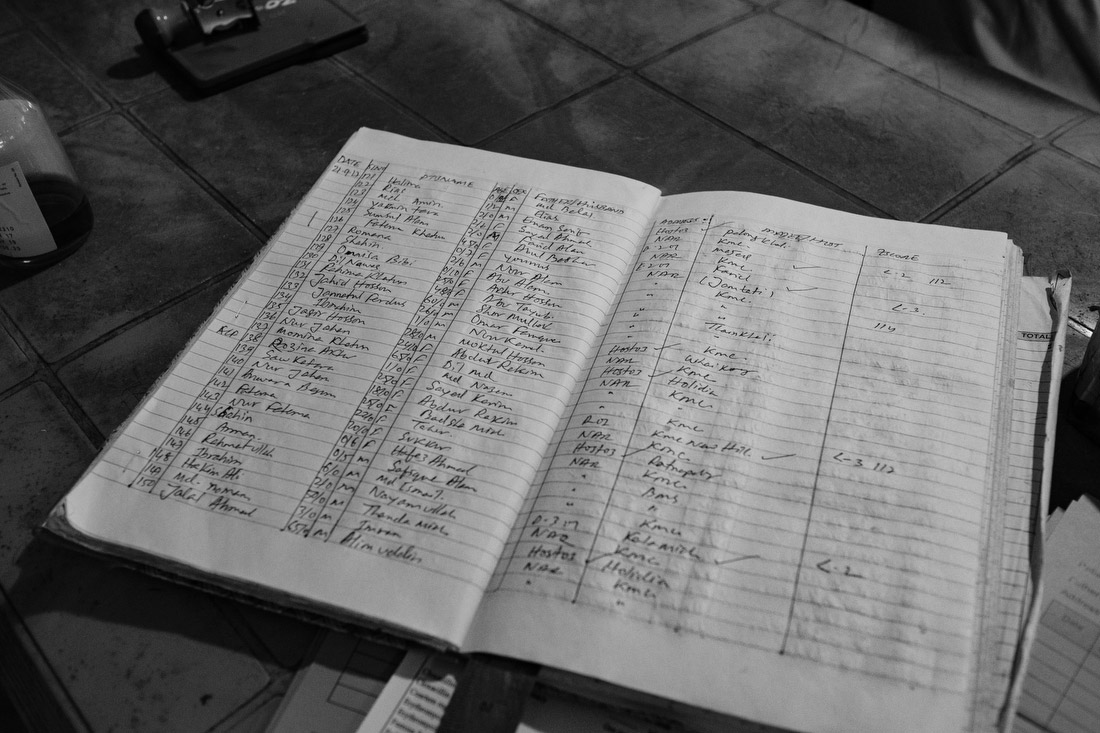

A list of children’s names is seen in a Doctors Without Borders clinic in the Kutupalong camp.

A woman with tuberculosis is transported in a basket by her two sons.

Children play soccer in the Kutupalong camp.

News Courtesy: www.cnn.com