In opposition of book censorship

LEARNING does not always lie in reading books that conform to ruling narratives. It can also be there in anti-orthodox thoughts and books that contain such thoughts. The concept of the geocentric, or earth-centred, model of the universe, which came to be known after Claudius Ptolemaeus, had been the ruling narrative since the ancient Greek period well into the Roman era. But the heliocentric, or sun-centred, model of the universe, which came to be known after Nicolaus Copernicus, supplanted the earlier model. The transition from the geocentric to the heliocentric model was not sudden and was not smooth. But the one with less acceptance replaced the more popular one, which most people that time thought to be true.

Galileo Galilei, a heliocentric model advocate who was an astronomer and not a theologian and is still considered a central figure in the transition from natural philosophy to modern science, could attract persecution and faced retribution by the church for his beliefs and thoughts in a period that was deeply marked by religion.

Similarly, learning does not always lie in good, or what authorities think to be good, books only. Knowledge can be gained from what is considered ‘wrong’ or ‘bad’ books by any governing body. The truth can be decided by reading falsehoods that any governing body opposes. No governing body should, therefore, have the power to decide whether reading materials are either good or bad for the public.

Any such power also contravenes with the proposition of free will, reasoning ability and individual, or even collective, conscience that are all innate in humans, which equip them to make decisions on their own on what to read and what not to, or what is right and what is wrong. Any such power also holds back the belief in people or society’s tolerance. When a few in society, with authority, decide reading materials for others, it chokes the space for arguments and counter-arguments that lead people and society to further rationalisation. This is also unfair on part of any governing body to do to writers, who create their works, mostly, with good intentions.

No one, perhaps, better knew the intricacies and coercion that lie in such restrictions. In his polemic called Areopagitica, John Milton, who had been censored when he tried to publish several treatises in defence of divorce, wrote in defiance of Parliament’s 1643 ‘Ordinance for the Regulating of Printing, or the ‘Licensing Order of 1643’. Areopagitica could not convince Parliament to remove the component related to prepublication censorship that he tried at in the Licensing Order, but the Puritan church adopted Milton’s pro-divorce ideas into its official charter. Prior restraint — or censorship before publication, that is — stopped his ideas from gaining wide acceptance.

This is what the Bangla Academy seems to be failing to understand what it should, rather, promote. Judgement on books is best left with readers. If there is any harm in any specific book, society with its collective conscience would reject it as it has always done. A ban on books does not also hold for long and in almost all cases, bans on books have only pushed up the sales of the books, mostly illegally, frustrating the purpose of the imposition of the bans.

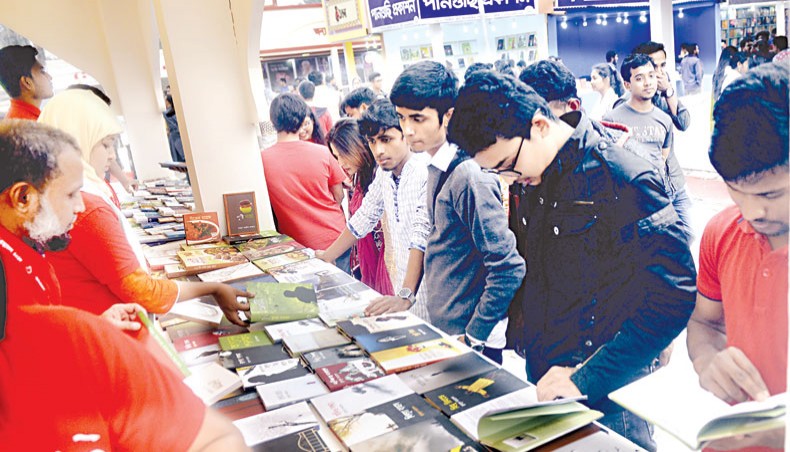

The Ekushey Book Fair began, as it did in the past, by the turn of January, with apprehensions by writers and publishers — this is the second time in a row — as the police are reported to have said, on January 25, that they would take steps if the academy, after scrutiny, recommends legal action against writers and publishers in cases of books on display in the fair that could hurt public sentiment. Although it is very difficult for the academy to go through about 4,000 books that usually hit the stalls and even if it could do that, the academy must not have the authority to censor books before they enter the market.

But books, nonetheless, continue to be banned, by the government for political reasons. Even Areopagitica, published in 1644, was banned by the Kingdom of England for political reasons. Yet this has remained to be a great essay ‘for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing’. George Orwell’s political novella Animal Farm, published in 1945, was banned in the USSR and in other communist countries. Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, published in 1949, was banned by the Soviet Union in 1950 and it was banned by the United States and the United Kingdom during the early 1960s. James Joyce’s Ulysses, published in 1922, had been banned in the United Kingdom until 1936. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, was banned in the Confederate States during the Civil War because of its anti-slavery content and it was banned in Russia under the reign of Nicholas I.

But they all have now came to be considered classics and are widely read by both ordinary people and literature enthusiasts. Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, published in 1988, was banned in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and some other countries. Humayun Azad’s Nari, published in 1992, was banned in November 1995 but the ban did not succeed in court in March 2000. Banned was also Taslima Nasrin’s Lajja, published in 1993. Kazi Nazrul Islam’s Yugabani, a collection of essays, was banned by the British Indian government in 1922. The next of Nazrul Islam’s books to face a ban was Bisher Banshi, a volume of poems, in 1924. All these books that have been, and were, banned only added to their readership. Some books not worth their names also came to be widely read just for the bans that they could draw.

Bans on books have hardly succeeded to stop them from reaching the readers. They ultimately reach the readers illegally. But the purpose of the imposition of the bans has, thus, almost always been defeated. Many of the books that were banned have now come to be regarded as great literary works, but many of the books that were banned have also come to be entirely forgotten. Bans on books can be a patchwork solution to head off troubles that could be otherwise managed, but they are by no means an effective device to keep books off the readers, or the readers off the books.

Authorities still try to stop books from reaching the readers by imposing bans, in a clear manifestation of authoritarianism. There are laws that apply to libel and other issues and they could be applied to printed materials but that should always take place with the sanction of court, after the examination of the arguments and counter-arguments and scrutiny of the contents.

French economist Thomas Piketty, writer of the bestselling Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which was named business book of the year for 2014 by the Financial Times, spurned the Legion of Honour, or Legion d’Honneur as they call it in France where it is the highest distinction, on grounds that it was not for the government to decide who is honourable — ‘I don’t believe it’s the role of the government to decide who is honourable.’

It is rare for anyone to turn down the award, as the BBC then wrote. But Picketty is not alone in rejecting the award. Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and a few others turned down the award. Edmond Maire, former leader of the pro-Socialist French Democratic Confederation of Labour union, refused the award, in the almost same language as Picketty’s — ‘it’s not up to the state to decide who is honourable or not.’

When authorities composed of a few with the power decide who are the honourable and who are not, they start thinking that they should also decide what are ‘wrong’ and what are ‘right’ for others to read. Milton, in his speech, said: ‘Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.’ It was in 1644. It has been long since. It is now for authorities to listen to it.

News Courtesy: www.newagebd.net