These North Korean defectors were sold into China as cybersex slaves. Then they escaped

Wearing big black headphones and sitting on a blue floral bedspread, North Korean defector Lee Yumi was video chatting with yet another stranger online, dark rings shading the pale skin under her eyes.

For five years, Lee -- whose name has been changed for her safety -- says she had been imprisoned with a handful of other girls in a tiny apartment in northeast China, after the broker she trusted to plan her escape from North Korea sold her to a cybersex operator. Her captor allowed her to leave the apartment once every six months. Attempts to escape had failed.

Lee's story is shared by thousands of North Korean girls and women, some as young as 9 years old, who are being abducted or trafficked to work in China's multimillion-dollar sex trade, according to a report by the London-based non-profit organization Korea Future Initiative (KFI).

North Korean women are often enslaved in brothels, sold into repressive marriages or made to perform graphic acts in front of webcams in satellite towns near cities close to China's border with North Korea, the KFI found. If caught by the Chinese authorities, they face repatriation to North Korea where defectors are often tortured. CNN was not able to independently verify claims made in the report.

Lee, however, had just found a lifeline. The stranger the 28-year-old was talking to online was not a cybersex customer. He was a South Korean pastor -- and he had promised to save her.

"Don't worry, we are going to rescue you," he said.

Lee smiled weakly and started to tear up, before typing back: "Thank you. I'm afraid."

Play Video

These North Korean defectors were sold into China as cybersex slaves. Then they escaped 03:35

Escape from North Korea

There are no official statistics showing exactly how many North Koreans have fled their country, which is home to about 25 million people. South Korea says it has welcomed more than 32,000defectors since 1998. Last year alone, the country received 1,137 defectors -- and 85% of them were women.

"It is much easier for them to flee, because they are not usually enrolled in formal employment at a factory or a state firm where any absence would be immediately reported," said Yeo Sang Yoon, from the Database Center for North Korean Human Rights, an NGO in Seoul. "They are in charge of the household and can thus slip away unnoticed."

Lee grew up in a family of low-level party cadres in North Korea.

"We had enough food," she said. "We even had rice and wheat stored in the garage." But Lee felt her parents were too strict. "I had to be home before sundown, and they didn't allow me to study medicine."

One day, after getting into a fight with them, she decided to cross the border into China. Lee said she found a broker to facilitate the dangerous move who promised her a job in a restaurant.

That promise turned out to be a lie.

Usually, women like Lee pay brokers $500 to $1,000 to organize their safe passage to China, according to NGOs and defector accounts.

To reach China, many defectors cross the Tumen River that separates North Korea from China on foot at night, sometimes in freezing weather with the water coming up to their shoulders.

After Kim Jong Un came to power in 2011, border security was tightened to avoid the bad publicity associated with defections and prevent information about North Korea trickling into the country, according to Tim Peters, an American pastor who co-founded an NGO called Helping Hands that helps defectors flee. An electric fence was added, as well as cameras at the border.

"On the Chinese side, patrols were also increased because Beijing is afraid an influx of refugees could destabilize its own regime," he added.

North Korea is visible from Yanji in China.

Two huge portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il hang at the entrance of a bridge linking the two countries.

Once on Chinese soil, defectors must reach the city of Tumen that sits right up against the icy river, in a lunar landscape of barren hills. North Korea is visible from the town -- farmers in a village there can be seen plowing their fields with antique machinery.

Lee crossed the Tumen River in a group of eight girls.

When she arrived in China, Lee said she was taken to a apartment on the fourth floor of a pale yellow building in Yanji, a city in Jilin province about 50 kilometers from Tumen, where most signs are written in Korean and Chinese and scores of restaurants sell bibimbap and kimchi, due to the large population of ethnic Koreans.

Yanji has a large population of ethnic Koreans. Many signs are written in Korean.

At the apartment, she realized there was no restaurant job.

Instead, Lee said her broker had sold her for 30,000 yuan (about $4,500) to the operator of a cybersex chatroom.

"When I found out, I felt so humiliated," she whispered. "I started crying and asked to leave, but the boss said he had paid a lot of money for me and I now had a debt towards him."

Korean NGOs estimate that 70% to 80% of North Korean women who make it to China are trafficked, for between 6,000 and 30,000 yuan ($890 to $4,500), depending on their age and beauty.

Some are sold as brides to Chinese farmers; more recently, girls have increasingly been trafficked into the cybersex industry, according to the KFI.

Rising wages in northern China cities have led to a greater demand for prostitutes among the male population, according to the KFI report. In southern China, trafficked women from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia has typically met that demand. But in northeastern provinces, men have turned to North Korean refugees.

A spokesperson for the Chinese government said in a statement to CNN: "I want to stress that the Chinese government pays high attention to foreign citizens' legitimate rights according to law, also combat activities of human trafficking women and child."

Michael Glendinning, director of the KFI, said the Chinese government was "not doing enough to protect North Korean women and girls in its territory at all."

"China must work to crack down on the networks and individuals -- including Chinese public officials -- responsible for the trafficking of North Korean women and girls, he said. "But it must do so in a way that ensures that these women and girls are not repatriated to North Korea where they would face torture, imprisonment, and possibly extrajudicial killing."

Two other North Korean women already lived in the two-bedroom apartment Lee was delivered to. One was 27 years old, had her own bedroom and seemed close to the chatroom boss. "I think she was supposed to spy on us," said Lee.

The other girl was Kwang Ha-Yoon, whose name has been changed to protect her identity for her safety. Kwang was 19 years old and had been locked up for two years when Lee arrived.

"My parents split up when I was very young and I grew up with my mother and grandparents," she said. "We never had enough to eat." Kwang left North Korea to earn money to send to her family. "Both my mother and my grandmother had cancer and needed treatment," she said.

But all the money Kwang earned in China went to her captor.

Lee and Kwang had to share a room.

"The only furniture was two beds, two tables and two computers," recalled Kwang. "Every morning, I would get up around 11 a.m., have breakfast and then start working until dawn the next day." Sometimes, she would only get four hours of sleep. If they complained, they would get beaten, although both women said they did not suffer sexual abuse by their captor.

Work involved logging onto an online chat platform on which South Korean men can pay to watch girls perform sexual acts.

Within minutes of logging on to the site, users are barraged by women on the platform sending text messages asking for a video chat in a private room.

They all claim to be from a major city in South Korea. The minimum price to chat on the site is 150 won (13 cents), but girls can set the entry price for a room, with popular accounts tending to have a more expensive entry fee. Tips start at a minimum of 300 won (25 cents), but can go far higher as customers try to persuade the girls to fulfill their requests. Lee and Kwang were tasked by their captors with keeping the men online for as long as possible. In South Korea, where prostitution is illegal, these services have become increasingly popular in recent years.

Many of the women working in the city's numerous K-TV and cybersex chatrooms are North Korean defectors.

CNN reached out to the platform to ask what steps it takes to protect women like Lee and Kwang on its site, but the company did not respond.

"Some of the men just wanted to talk, but most wanted more," said Lee, with a shudder of disgust. "They would ask me to take suggestive poses or to undress and touch myself. I had to do everything they asked."

"I felt like dying 1,000 times, but I couldn't even kill myself as the boss was always watching us," she said.

Her captor was a man of South Korean descent who slept in the living room to keep a close eye on the women.

"The front door was always locked from the outside and there was no handle on the inside," said Kwang. "Every six months, he would take us out to the park."

On this small patch of green next to their apartment, retirees would meet to dance to music each afternoon.

The park where the chatroom boss would sometimes bring them, right next to the building where they were held.

"During those outings, he would always stay right next to us, so we never got to talk to anyone," said Lee. In 2015, Lee tried to escape by climbing out of a window and down a metal drain, but she fell and hurt her back and leg. She still limps slightly.

When their captor wanted something from the girls, he would try to sweet talk them, promising a cut of their earnings or to let them go free to work in South Korea one day.

But when Kwang asked for a piece of the 60 million won (around $51,000) she estimated she had made for him, he got angry.

"He started kicking, slapping and cursing me," she said.

During the seven years Kwang spent locked up in his apartment, she said he never gave her a cent.

A ray of light

It was during the summer of 2018 that Lee finally saw her chance to escape.

"One of my customers realized I was North Korean and was being held captive," said Lee. While most men probably knew the girls weren't South Korean, because North Koreans have different accents and dialects to people in the south, they chose to look the other way.

This man was different.

"He bought a laptop and let me take control of the screen remotely, so I could send messages without my boss noticing," Lee said.

The man also gave her the phone number of a South Korean pastor named Chun Ki-Won.

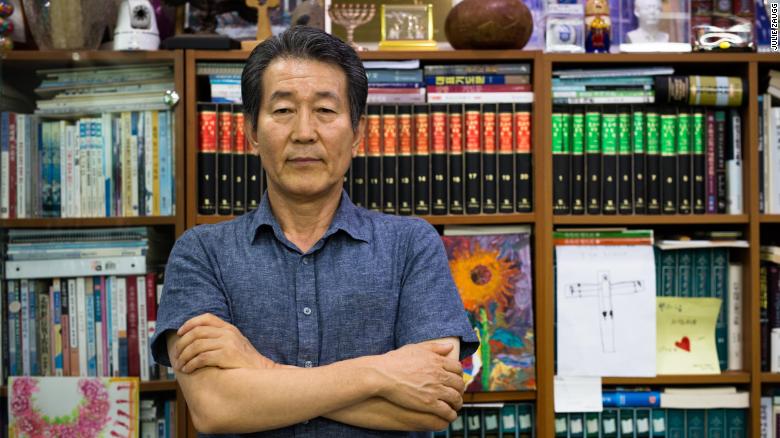

Pastor Chun Ki-Won has been helping North Korean defectors flee for 20 years. He has been nicknamed the Asian Schindler.

Chun, a mild-mannered man with high cheekbones and wavy gray hair, is one of a band of Korean pastors who specialize in helping North Korean women escape from China. Chun said his Christian aid organization, Durihana, has helped over 1,000 defectors reach Seoul since 1999. Korean media has nicknamed him the Asian Schindler, after the German industrialist and Nazi Party member who saved the lives of 1,200 Jews.

"In the past few years, dozens of missionaries linked to my organization have been deported from China," he said from his Seoul office that overflowed with plants, books and religious figurines. "There are only a few left, and they have to stay on the move constantly to avoid being arrested."

China is a close ally of Pyongyang and doesn't consider North Korean defectors refugees, instead seeing them as

Lee and Kwang met with a Chinese man who took them across the mountains into a neighboring country.

In total, they said their journey from Kunming took 50 hours.

A few minutes later, Chun walked out -- alone.

Before entering the South Korean Embassy, Lee had given her new life a lot of thought.

"I want to study English and Chinese and maybe become a teacher," she said.

Kwang, who had left school at 12, hoped to graduate.

"I never really had the luxury of wondering what to do with my life," she said.

News Courtesy: www.cnn.com