US policy, pre-emptive force and Qasem Soleimani

INTERNATIONAL relations is typified by its vagueness of definition and its shallowness of justification. Be it protecting citizens of a state in another, launching a pre-emptive strike to prevent what another state might do or simply understanding the application of a treaty provision, justifications can prove uneven and at odds.

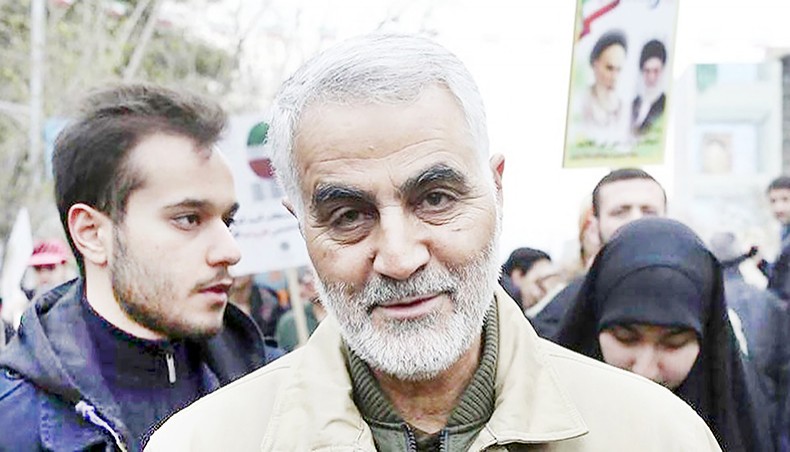

The pre-emptive jerk behind the killing of major general Qasem Soleimani of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps-Quds Force was one such occasion. (It transpires that there was another effort, failed as it turned out, against the Quds commander Abdul Reza Shahla’i.) The ingredients behind the drone strike were supposedly clear: the now vanquished leader of the Quds operational arm was planning attacks on US soldiers and interests. In any case, he had killed many US personnel before. The attack could therefore be seen as an adventurous, and advanced reading, of self-defence, billed by the legal fraternity as ‘anticipatory self-defence’.

Article 51 of the United Nations Charter qualifies the use of force against another state by imposing two conditions. There must be authorisation by the Security Council to use force to maintain or restore international peace and security. The second arm of the provision legitimises the use of force where a state is exercising its recognised right to individual or collective self-defence. But the boundaries of the latter are often unclear; they include ‘preventive’ military action and ‘pre-emptive’ military action, with the former focused on targeting the enemy’s acquisition of a capacity to attack, the latter focusing on foiling an imminent enemy attack.

Both the United States and Iran duly resorted to Article 51 letters in light of Soleimani’s killing. US ambassador to the UN, Kelly Craft, claimed that the strike took place as a response to an ‘escalating series of armed attacks in recent months’ by Iran and its proxies on US personnel and interests in the Middle East ‘in order to deter the Islamic Republic of Iran from conducting or supporting further attacks against the United States or US interests’. The additional purpose of the attack was to ‘degrade the Islamic Republic of Iran and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Qods Force-supported militias’ ability to conduct attacks.’

Iranian ambassador Majid Takht Ravanchi obliged with a counter letter to the UN justifying its January 8 actions in retaliation against a US airbase in Iraq for the killing of Soleimani. The retaliatory strikes were deemed ‘measured and proportionate’, ‘precise and targeted’ and left ‘no collateral damage to civilians and civilian assets in the area.’

For all the padding offered, the Soleimani killing could be considered a legacy of a tenuous and precarious reading of self-defence offered by the United States since 2001. US policy makers have done their obfuscating bit to compound the sheer vagueness of anticipatory self-defence since president George W Bush occupied the White House. The US National Security Strategy of 2002, followed by its 2006 variant, showed the sloppiness that comes with imperial overconfidence in the pursuit of enemies. Pre-emption and prevention lose their distinct forms when the drafters search for legitimate uses of force against a shady enemy that prefers to play by different rules.

NSS 2002 acknowledges that centuries of international law ‘recognised that nations need not suffer an attack before they can lawfully take action to defend themselves against forces that present an imminent danger of attack.’ But the scope is given a good widening. ‘The United States has long maintained the option of pre-emptive actions to counter a sufficient threat to our national security. The greater the threat, the greater is the risk of inaction — and the more compelling the case for taking anticipatory action to defend ourselves, even if uncertainty remains as to the time and place of the enemy’s attack.’

Embracing such a broad reading of pre-emption was conditioned by ‘the capabilities and objectivities of today’s adversaries. Rogue states and terrorists do not seek to attack us using conventional means.’ So it goes: the enemy obliges us to adjust, alter and repudiate conventions. Flying civilian planes into the Twin Towers in New York on September 11, 2001, constituted such an unconventional manner of attack.

The 2006 National Security Strategy stated unequivocally that ‘the place of pre-emption in our national security strategy remains the same’ though conceding that ‘no country should ever use pre-emption as a pretext for aggression.’ Using such force would take place after ‘weighing the consequences of our actions. The reasons for our actions will be clear, the force measured, and the cause just.’ Four years later, under the Obama administration, the position had not much improved, and the muddle remained.

The killing of a senior Iranian commander in circumstances that could hardly be seen as a matter of combat revived that hoary old chestnut of imminent threat. When US secretary of state Mike Pompeo was pressed about the nature of such imminence in a press conference, the old tangle of interpretations became manifest. ‘Mr Secretary,’ came one question, ‘the administration said this strike was based on an imminent threat, but this morning you said we didn’t know precisely when and we didn’t know precisely where. That’s not the definition of ‘imminent’.’

Pompeo was not exactly helpful, resorting to the classic rhetorical device of circularity. ‘We had specific information on an imminent threat, and those threats included attacks on US embassies. Period. Full stop.’ He conceded to not knowing, with exact precision, ‘which day it would’ve have been executed. I don’t know exactly which minute.’ But the evidence was sound enough: Soleimani ‘was plotting a broad, large-scale attack against American interests. And those attacks were imminent.’

Each time he was confronted with a question on clarification, Pompeo dissembled. In not taking any action to stall the efforts of Soleimani, the Trump administration ‘would have been culpably negligent’ in not recommending the president to ‘take his action’.

President Donald Trump, for his part, has given the impression of justified clarity. ‘I can reveal,’ he told Fox News, ‘that I believe it would have been four embassies.’ Before a campaign rally in Ohio on Thursday, he suggested that Soleimani had been ‘actively planning new attacks, and he was looking very seriously at our embassies, and not just the embassy in Baghdad.’

None of this really matters in the final analysis. Uses of force must be justified after the fact, and the tradition of big power statecraft shows that the more formidable a power, the more likely threats against it will be magnified. The attack on Soleimani had as much to do with inflated claims of US security as it did with chronic insecurity.

CounterCurrents.org, January 13. Dr Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne.