China is about to pass a controversial national security law in Hong Kong. Here's what you need to know

China is introducing a sweeping national security law for Hong Kong that has sparked protest, fear and controversy in the semi-autonomous city.

Critics say the law, which in some cases could overide Hong Kong's own legal processes, marks an erosion of the city's precious civil and political freedoms; the Chinese and local governments argue it's necessary to curb unrest and uphold mainland sovereignty.

Everything has unfolded at breakneck speed. Beijing only introduced the proposal a month ago, and the law is expected to go into effect by July.

Here's what you need to know about the bill -- and what it means for the city.

What is the law, and who's behind it?

Beijing has been asking Hong Kong to pass a national security law since 1997, when the former British colony was handed back to China. There's even an article in the city's mini-constitution calling on it to do so.

Hong Kong politicians have attempted to pass the legislation before, but faced fierce public opposition.

On May 22, Beijing decided to take matters into its own hands, and proposed the bill for Hong Kong at the National People's Congress (NPC), China's rubber-stamp parliament.

While Hong Kong has an independent legal system, a back door in its mini-constitution allows Beijing to make law in the city -- meaning there's not much the Hong Kong public or leadership can do about it.

Under this proposed law, criminal offenses will include secession, subversion against the central Chinese government, terrorist activities, and collusion with foreign forces to endanger national security, according to Chinese state-run Xinhua news agency.

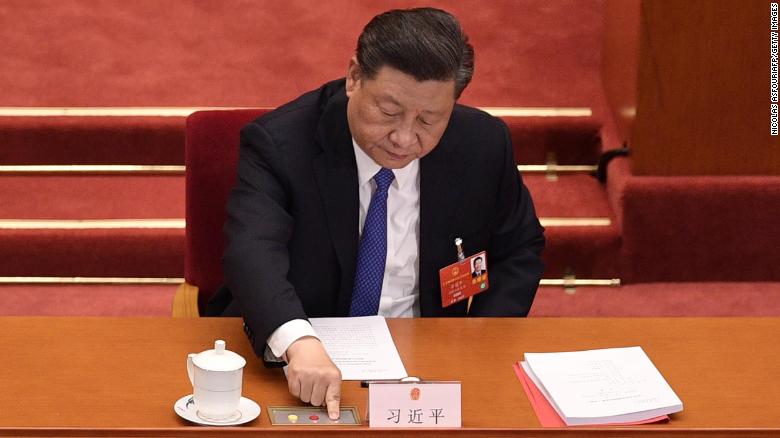

Chinese President Xi Jinping votes on a proposal on the Hong Kong security law during the closing session of the National People's Congress in Beijing on May 28.

What would the law do?

The law will allow mainland Chinese officials to operate in Hong Kong for the first time and give Beijing the power to override local laws.

Under the proposed law:

- Beijing will establish a national security office, staffed by mainland security services to supervise local authorities in policing the law, according to Xinhua.

- Hong Kong's top official will pick which judges hear national security cases, jeopardizing the city's independent judiciary.

- Mainland Chinese authorities can "exercise jurisdiction" over cases in special circumstances, meaning certain crimes in Hong Kong could result in trials on the mainland.

- The city will set up a national security commission, with a Beijing-appointed adviser and operating under "the supervision of the central government."

- The bill trumps local laws. If there is a conflict with existing Hong Kong law, the national security law prevails.

What are the unanswered questions?

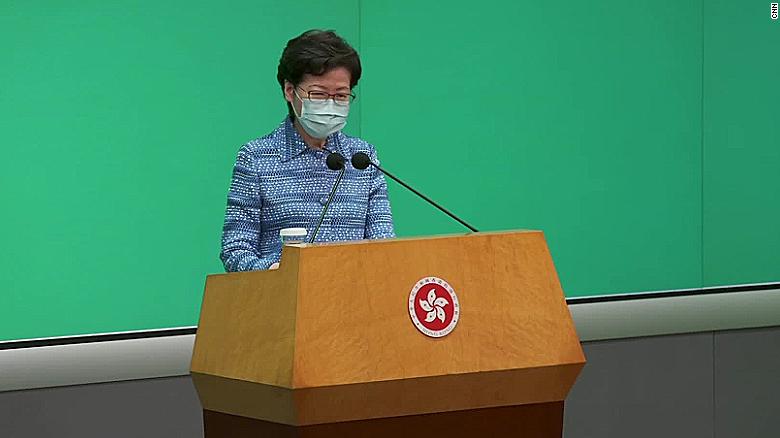

There's still a lot we don't know. Much of the drafting process happens behind closed doors, and there has been no public consultation on the bill -- even Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam, the city's top official, said she hasn't seen the "complete details."

It's not yet clear how well-defined these crimes will be, or what exactly will constitute broad terms like foreign collusion or subversion.

We still don't know how the law will protect the rights of the accused, and which special circumstances will prompt the Chinese authorities to step in or require the extradition of suspects to the mainland.

It's also not clear whether there will be any checks and balances that allow the local government to regulate what mainland agents do in Hong Kong, and what role those agents could play in any potential political prosecution of city opposition figures.

Why didn't Hong Kong pass the law itself?

The local government tried to pass a national security law in 2003, but after massive protests, they shelved the legislation and no administration has dared to try again, much to China's frustration.

Hong Kongers back then had the same fears as they do now -- that a national security law could infringe on their freedoms and be used to crush dissent.

Then the 2019 protests happened, this time against another bill that would have allowed suspects in Hong Kong to be extradited to the mainland. Many Hong Kongers once again feared that Beijing was extending its reach into the city's independent judicial system.

For more than six months, Hong Kong was rocked by often violent pro-democracy, anti-government protests, which posed a major challenge to the city's local leaders and police force, who deployed tear gas and water cannon.

Beijing's patience, long frayed by the local government's failure to pass the law, ran out -- so the central government took action into its own hands.

Before we dive deeper, some background

Though Hong Kong is part of China, it enjoys more liberties than any other Chinese city.

Hong Kong was a British territory until it was handed back to China in 1997. The handover agreement gave the city special freedoms of press, speech, and assembly, protected for at least 50 years, in a model of governance called "one country, two systems."

Under this model, Hong Kong also has its own currency, judicial system, identity and culture -- freedoms that stand in stark contrast to China's censorship and authoritarian rule in the mainland.

Hong Kongers have long feared Chinese encroachment on their autonomy, and have pushed for greater democracy -- one of the driving factors behind last year's protests, as well as the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

Why is this law so controversial?

The law drastically broadens Beijing's power over the city and could change daily life and society.

Many worry the law could be used to target dissidents, a fear that stems from China's judicial track record.

In the mainland, national security laws have been used to prosecute pro-democracy campaigners, human rights activists, lawyers and journalists. Arbitrary punishments and secret detentions are almost unheard of in Hong Kong -- but people worry this new law could change that.

Critics say the law could also cause increasing self-censorship in the media, the exclusion of pro-democracy figures from the city's legislature, and threaten Hong Kong's reputation as a safe base for international businesses.

All of this remains speculation until the law is enacted and used, but it represents what Hong Kongers are most afraid of -- the end of their freedoms and of "one country, two systems."

What have Hong Kongers said?

China's announcement of the law was met with fierce resistance from much of Hong Kong society.

After it was announced, crowds of protesters returned to the streets and clashed with police, who again fired tear gas and deployed water cannon.

Pro-democracy lawmakers including Claudia Mo condemned the law as "taking away all the core values we've come to know," while the Hong Kong Bar Association blasted the law as a major blow to judicial independence.

Some Hong Kongers have told CNN they are considering fleeing the city to safer shores like the self-governing island of Taiwan, where authorities set up an office to help Hong Kong citizens moving there for "political reasons."

But some have also welcomed the law. Business officials have argued it could bring much-needed stability to the city after last year's unrest, which devastated the city's economy, shuttered scores of stores and restaurants, and damaged Hong Kong's international reputation. HSBC and Standard Chartered, two of Hong Kong's biggest banks, both support the bill.

A protester is detained by riot police in Hong Kong on May 24.

What has the Hong Kong government said?

Lam, Hong Kong's leader, said the central government had "no alternative but to take action" after last year's political unrest, and that Hong Kong had a "constitutional duty" to uphold China's sovereignty.

She has repeatedly denied the law will infringe on citizens' basic rights, stating that it will not undermine the city's "judiciary independence and high degree of autonomy."

Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung, Hong Kong's second-highest ranking official, has also insisted that only terrorists and separatists will be targeted by the law -- but he has little influence in the drafting the details.

Hong Kong Police Commissioner Chris Tang told Chinese state broadcaster CCTV in May that the law "will not affect Hong Kong people's rights and freedom" and will help the city "become more stable and safe."

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam at a press conference in May after the announcement of the proposed bill.

What have other world leaders said?

The proposed law has been met with concern and condemnation from the international community; more than 200 lawmakers from 24 countries have signed an open letter in opposition to the bill.

US President Donald Trump blasted Beijing for the law and revoked Hong Kong's special status on trade, saying in May that the US will apply the same restrictions to the territory it has in place with China.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson argued the law "would curtail (Hong Kong's) freedoms and dramatically erode its autonomy," and promised to provide a path to British citizenship for potentially millions of Hong Kongers.

The leaders of the European Union (EU) expressed "grave concerns" about the potential threat to fundamental rights and freedoms. Lawmakers in the European Parliament warned that China was violating its international commitments, and proposed bringing China before the International Court of Justice.

News Courtesy: www.cnn.com